If things go wrong or if a team member receives a complaint about end of life care, it is important that there is a mechanism within your service to deal with this.

If a formal complaint has been made, you may be asked to respond. All services should ensure that action plans are put in place following investigation of a complaint. Check your local guidelines and policies for this.

If things go wrong and no formal complaint is received it is still important for your team to learn from this. Being open and honest with families and patients when issues arise is extremely important. Most people who make an informal complaint want some acknowledgement that their concern has been taken seriously or apology from staff. These issues can be discussed at mortality and morbidity meetings.

If an individual member of staff receives a complaint against them they should be supported by the organisation during the process which can be very stressful. Always refer to your local policy and procedures.

If end of life care does not go well, it is important to discuss and learn as a team in a non-threatening, no-blame environment. For example, see left.

Review feedback from families who have been through the end of life after stroke process. Include positive and negative comments to learn what your team does well and where you need to improve.

Jimmy was admitted to the hyperacute stroke unit to monitor his condition. His blood pressure was initially very high, so he was treated with intravenous GTN for 24 hours and then switched to oral blood pressure lowering medication.

He was stable so was repatriated for further stroke unit care to his local (spoke) hospital. He made a good recovery and is now living back home with his wife. He is taking more exercise and is trying to stop smoking. He is hoping to get back to fishing soon.

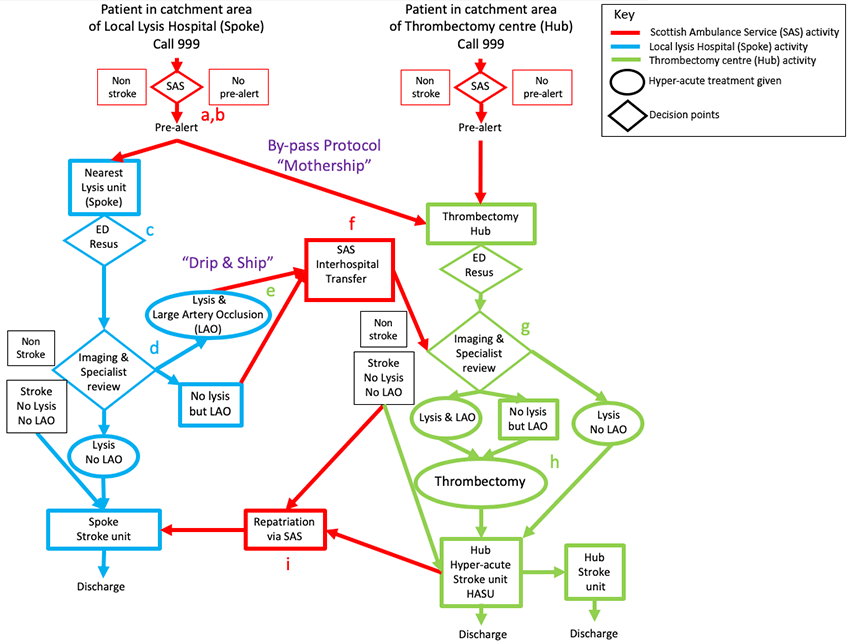

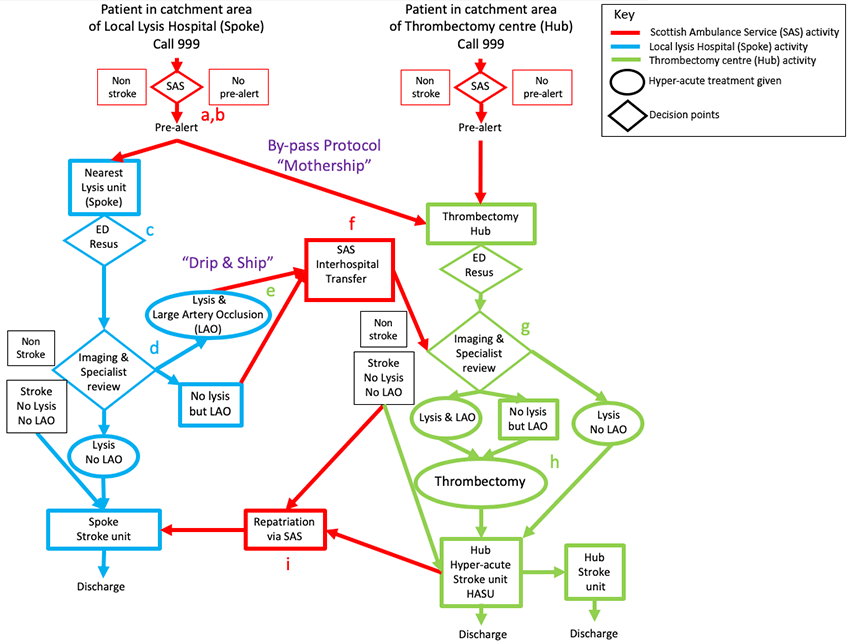

Here is the complex diagram showing the possible pathways to thrombolysis and thrombectomy we saw in the Introduction to this module.

Jimmy’s pathway

Select True or False for each statement about Jimmy’s actual pathway.

Note these are not specific to end-of-life care.

Unhelpful comments

- Oh, that’s the lady with the neurotic daughter.

- That’s her alcoholic son … he’s always drunk.

- The family just don’t seem to ‘get it’ that he is dying.

- I’ve never met such a demanding family before.

- The patient is ‘doolally’ … He thinks there are tigers in his room!! (note this is probably because the patient has an undiagnosed delirium which is quite common when people are dying) .

- That’s the Professor. He insists on us calling him ‘Professor’ (respect how patients wish to be addressed – and don’t assume that all patients or families are happy to be called by their first name).

- That man has become part of the furniture … do you think the social worker will ever come to see him so we can get him discharged?

Better comments

- Her daughter is her main carer – she’s really upset and worried about her mother.

- We wonder whether her son has been drinking? He seemed unsteady when he came in.

- The family are finding it hard to understand what we’re saying and what’s happening.

- The family need a lot of support.

- I’m worried that Mr X might be delirious. He’s hallucinating and it’s very upsetting for him and his family

- Professor X used to be the Professor of Physics. He is a private person and has asked that we address him as Professor – please can we make sure that staff are aware?

- We have discussed with Mr V and his family and we are all keen to discharge Mr V as soon as possible. Has the social worker been in contact about this?

Here we discuss the sort of comments which can be unhelpful and offer some examples of alternative more helpful comments.

Not so useful

- ‘She’s for comfort care’, (too vague)

- He’s palliative’ (too vague);

- ‘We’re stopping feeding’ (not clear what sort of feeding )

- ‘We’re withdrawing active treatment’ (not clear what specifically this means; and using the term ‘withdrawing treatment’ could imply ‘withdrawal of care’)

- ‘She’s not for escalation’ (not clear what this means-could instead say ‘ward level care’ and not for CPR)

- Consultant to junior doctor: ‘please update the family’ (following an MDT)-(this is too vague-specify what family need to be updated about)

More useful

- Family and staff agreed a trial of antibiotics with a review in 48 hours (clear with a time frame)

- Staff nurse X and Doctor Y have booked a meeting on … with Mr Z wife and son to discuss next stage of care plan. (specifies who & when and what is being discussed)

- DNACPR form has been discussed with patient and signed on …. Now filed in case notes (Important information simply explained)

- Family have been given a demonstration by speech and language therapist to offer small sips of puree and thickened fluids safely when visiting. Family have also been informed about aspiration risk. (Shows family have been fully informed)

- Mr Z has requested no further attempts to pass nasogastric tube but has agreed to subcutaneous fluids and small sips of water. (specifies the treatment plan which patient has been involved in the decision making)

Multidisciplinary team meetings are a key part of stroke unit care. Most teams meet at least weekly, sometimes daily to have brief, focussed discussions about future care. These meetings are important opportunities to make decisions about end of life care.

It is important that each team member comes to the meeting with information about how each patient is progressing and any interactions with families which may influence end of life decisions or care and be prepared to talk about this. During the meeting it is important for everyone to have the opportunity to have their say even if you agree or disagree.

Finally it is important that the outcome of the meeting is clearly documented in the notes so that other staff who were not present can quickly find out about the agreed actions.

At the end of the discussion about each patient, ensure that decisions are documented clearly and specifically. For example:

- No intravenous fluids

- No antibiotics

- Oral feeding and thickened fluids accepting the risk of aspiration

- No further observations

- The rationale for the overall strategy. Note that the rationale for decisions (as well as the decisions themselves) will form the basis of subsequent discussions with the families

- Document whether decisions are still pending e.g. ‘will review next week whether to discontinue NG feeding’

- Also note who will be responsible for contacting the family to discuss the decisions made by the team

Ensure that families’ current concerns are discussed. These may be immediate issues such as pain or dry mouth, as well as discussing longer term plans.

In Scotland a system called Key Information Summary (KIS) is available to assist in communicating important information about care which can be securely shared with a range of healthcare professionals and out of hours services.

KIS is only available in Scotland.

What is KIS?

Key Information Summary (KIS) is an extension to the existing Emergency Care Summary (ECS). It is created by the GP and with consent of the patient. It is designed to support patients with long term conditions or who have an advanced care plan in place. Information is available to ECS users in NHS 24, out of hours organisations, accident and emergency units, the Scottish ambulance service and hospices.

The KIS usually includes the following information:

- Medication

- Allergies or reactions to medicines

- Contact information

- Care plans

- Next of kin and carer details

- Wishes or special instructions for care

- Management plans if the person has a long term condition or advanced care plan.

- Preferred place of care

Each entry to the KIS is dated at the point when the item was added and any changes must be dated accordingly. Patients may also keep a printed copy of their own KIS information and carers are informed that their details have been added to the KIS.

For any patient the following information should be included in any planned discharge to allow patients who want terminal care at home with support, provided this is safe and possible to arrange.

- Acute diagnosis and functional status at discharge

- Any communication or memory problems

- Prescribing updates

- Current health and social care needs, including an anticipatory care plan

- Follow up plans / visits by stroke nurse

- Patient’s and carer’s understanding of likely course of events

- Preferred place of care, and of final care if discussed

- DNACPR status

- Request to start of update a KIS using above and other data

It is important not to underestimate the importance of good communication after death.

- If this occurs out of hours and the patient’s own team is not available, the on-call team and nursing staff should speak to the family, express sympathy, answer any immediate questions the family may have and explain the processes for obtaining the death certificate and making funeral arrangements. If the Procurator Fiscal (Scotland) or Coroner (England) or equivalent needs to be informed about the death, ensure the family are aware. This requires local knowledge of criteria for referral.

- The death certificate should be given to the family by a senior member of the patient’s own team (ideally the consultant), explaining what is written on it and giving the family time to ask questions.

- The meeting should not be rushed, and should be held in a quiet room.

- Families often remember the detail about how this interaction went. If it is done well, this is very helpful to families.

Consider whether to communicate a few weeks later e.g. a phone call or bereavement card 6 weeks later with an invitation to speak to family again.

- Some services do this routinely.

- Families who take up the offer of another meeting often find it helpful to clarify aspects of the patient’s care, particularly if the patient died quickly and there was little time for discussion with staff.

- Families who have unresolved concerns about care provided (but for whatever reason had been unable to raise this before) may take up this opportunity if invited. If this is not offered they may feel that the only way to address their concerns is through the formal complaints system.

- Mrs McCrory is a 94-year old lady with early dementia who lives in a nursing home. Widowed. She presented with a stroke 3 weeks ago that led to dysphagia, dysphasia and right arm weakness.

- She has been NG fed for the last 3 weeks but has not tolerated the NG tube well. She has repeatedly pulled the tube out and finds it distressing to have it reinserted. It is not clear whether this is her way of saying that she no longer wants to be treated or whether it’s because the tube is uncomfortable. She does not attempt to swallow when given teaspoons of soft food.

- Prior to this stroke and her onset of dementia she had always maintained that she would not like to have treatment to prolong her life if she was going to be dependent and would prefer to die.

- She can answer yes/no to questions but these are not consistent.

- You feel that repeated attempts at inserting an NG tube (or PEG tube) would not be in her best interests and against her previously expressed wishes.

- The family have not expressed any views about preferred place of death, but you also want to discuss whether to let her go back to her nursing home. Daughter lives locally and visits often, her son works away and sees his mother about twice a year.

Meeting with doctor, nurse and daughter. The multidisciplinary team have all met and are in agreement that stopping NG feeding would be appropriate. Sometimes getting a second consultant opinion can be helpful if there is any doubt within the team or if the family disagree. There was consensus amongst the team and so a second opinion has not been sought-but the doctor is prepared to offer this if the family seem uncertain.

The following case study video contains interactive elements. If you are having issues with opening the interactive video, please follow one of the alternative video links below. The patient in this case is fictional but is based on real cases.