- Sedentary behaviours complicate the recovery process and affect risk of recurrence. It is a challenge to establish a safe therapeutic exercise regimen to firstly regain previous stroke activity and secondly to reach sufficient activity to reduce stroke risk. Activities should be matched to ability, interests and availability.

- Find out what is available in your area and be creative!

- Bums off seats / seated exercise / bowls / golf / dancing / tai chi/ yoga / walking / cycling / gardening

- Think about types of activity for stamina, strength and flexibility and mobility (see CHSS leaflet )

- Application of Wii-Fit (Wii-Hab)

- Barriers to activity:

- Lack of interest, social support, time, opportunity, transportation, financial means

- Physical difficulties including paresis, shortness of breath, joint pain

- Dislike going out alone

- Perceived lack of fitness

- Lack of energy

- Doubting that exercise can lengthen life and lack of knowledge that exercise is beneficial to health

- There can be many barriers to people participating in activity. Think about using brief interventions to identify what might be suitable. Try to offer alternative types of physical activity.

Category: Topic Loops

Physical fitness

Physical fitness – a set of attributes which people have or achieve that confers the ability to perform physical activity

- Physical fitness is important for the performance of everyday activities. The physical fitness of stroke patients is impaired after their stroke and this may reduce their ability to perform everyday activities and exacerbate any stroke-related disability.

- In theory physical fitness training after stroke may:

- Improve function

- Reduce disability

- Improve quality of life

- Improve mood

- Reduce fatigue

- Reduce the risk of falls

- Improve vascular risk factors and so reduce risk of recurrent stroke and death

- Aim for at least 150 minutes (2 ½ hours) of moderate physical activity a week. For example, 30 minutes on 5 or more days, or a few sessions each day of 10 minutes at a time. Or

You could do 75 minutes of vigorous activity a week instead. Moderate activity is activity that increases your breathing and heart rate. It makes you feel warm but you are still able to talk. For example, swimming, walking quickly, cycling. Vigorous activity is activity that makes your breathing fast and talking difficult. For example, running, playing sport, hiking uphill. For more information see CHSS: Physical Activity.

Relationship to stroke

- There is substantial evidence to support the beneficial effect of regular physical activity on risk factors for stroke including hypertension, glucose intolerance, low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations and obesity.

- Physical activity may reduce the risk of stroke (both ischaemic and haemorrhagic) and is an important modifiable risk factor (this evidence was in relation to primary prevention but it is reasonable to extrapolate from this that there will be a secondary prevention effect).

- There is a direct and dose respondent relationship between blood pressure and stroke risk.

- Activity helps to lower BP and improve lipid profiles, improve endothelial function and vasodilation and reduces blood viscosity, fibrinogen levels and platelet aggregability.

- Moderately active people have 20% lower risk of stroke.

- Highly active people have 27% lower risk of stroke.

Physical activity

Headlines

Approaches to treatment

- PFO associated with stroke is relatively uncommon so we lack relaible evidence about which treatment are best.

- The risk of recurrent stroke is only about 2% per year – so RCTs need to be very large with long follow up to demonstrate that a treatment has reduced this risk significantly.

- Aspirin (or other antiplatelet drug) – relatively safe and well tolerated.

- Anticoagulation – likely to reduce clots but associated with significant bleeding risk and Warfarin is inconvenient. Young patients face many years of treatment.

- Percutaneous closure of PFO – PFOs can be closed during a cardiac catheter procedure. This procedure carries risks of arhythmias, bleeding and embolism of the closure device.

- Decisions about treatment need to take account of an individual assessment of the patients risks and take account of their beliefs and concerns.

Quiz

Patent foramen ovale

Introduction

- A patent foramen ovale (PFO) is present in all babies prior to birth (to allow blood to by-pass the lungs which are not used in utero) – in 80% of people it closes after birth

- It occurs in about 1 in 5 (20%) healthy individuals.

- It is associated with about a 3 fold (relative risk = 3) risk of stroke in younger adults.

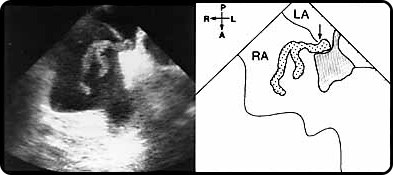

- It may provide a route for so called “paradoxical emboli” to move from clots in the veins to the brain by by-passing the lungs which usually filter out clots. The illustration below shows a large clot going through the PFO.

- It can be detected by a transthoracic or trans-oesophageal echocardiogram with bubble contrast (see video of bubbles crossing septum) or transcranial Doppler.

Duration: 10 seconds

References

- Royal College of Physicians (2016)

- Townend, E., Brady, M., & McLaughlan, K. (2007). A Systematic Evaluation of the Adaptation of Depression Diagnostic Methods for Stroke Survivors Who Have Aphasia. Stroke; 38: 3076 – 3083.

Which of the following actions are appropriate and which are inappropriate when carrying out mood screening?

How can these tools be used with people with aphasia?

- If someone has a communication problem then adaptations can be made to the assessment.

- Adaptive methods included:

- using informants (relatives or staff)

- increased reliance on clinical observation

- modifying questions (simplifying to yes/no answers)

- visual analogue scales.

- See Townend, Brady, & McLaughlan (2007) for a systematic review.

- Smiley faces or observational criteria on their own should not be used diagnostically (RCP, 2016).

- Similar adaptations could be used for those with significant cognitive impairment that is affecting assessment.

- Consideration should also be given to those with visual and visuospatial problems where horizontal (left to right) visual analogue scales may be difficult to interpret.